As a 3D artist, I try to take inspiration from many different sources to help improve and refine my work. A lot of the time this can be quite technical, and keeping up to date with the latest software and hardware is important. To make beautiful compelling images takes more than technical know-how.

I’m going to have a look at a couple of powerful examples of production design from the world of cinema, where the set or environment itself helps to drive the plot, has a story of it’s own, or in some cases is the focal point of the whole film. In examining this, we should be able to gain some insight into what makes a successful narrative environment.

Brazil (1985) directed by Terry Gilliam is a science-fiction fantasy film that tells the story of Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce), a lowly office clerk trapped in a dystopian bureaucracy. The dysfunctional government controls every aspect of life, with even the simplest tasks requiring reams of paperwork to complete. His only escape from his claustrophobic surroundings is daydreaming about slaying a monster to rescue a beautiful woman.

The film takes place in a surreal retro-futuristic cityscape, which has been described by Gilliam as "Neither future nor past, and yet a bit of each. It is neither East nor West, but could be Belgrade or Scunthorpe on a drizzly day in February." The totalitarian government in the film warns the public to be vigilant regarding terrorist attacks, but it is actually the shoddy workmanship of Central services causing much of the damage. The ubiquitous ducts present in nearly every scene show the bodged and thoughtless nature of many of their repairs. There is very little colour in the film, and it is mostly filmed in drab blacks, whites and greys, to make the environment feel as though it has been drained of life.

In one memorable scene Sam is shown to his new office, which is a tall, narrow, grey space with nothing but a small desk, which intersects with the wall. He takes his place at the desk and begins to organize his things. The desk starts to move, and Sam has to fight to keep his half, as the man in the office next door is physically pulling it through the wall.

This can be seen again in the film’s approach to industrial design, with everyday items such as telephones and computers becoming unwieldy incomprehensible devices. The telephone becomes a muddled knot of plugs and wires more like an archaic switchboard than a sleek electronic device, and the computers are modified typewriters with fuzzy little screens magnified by another, larger screen, rather than just having one large screen.

Through the environment we get the sense that simply trying to exist in this world is a grinding struggle, where the only sane response would be to escape into a dreamworld. The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) directed by Wes Anderson, is a very different film to Brazil, but the story is told through the environment. The film is told through a flashback from 1968, looking back at the hotel’s glory days in the early 1930s. It tells the story of the Hotel’s legendary concierge M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) as he gets accused of murdering a wealthy guest, and Zero Moustafa (Tony Revolori), the lobby boy who becomes his most trusted friend.

The hotel itself is an enormous spa and ski resort, set in a fictional Central European country called the Republic of Zubrowka. It sits above a small village halfway up a mountain, and is reached via a funicular railway. It is styled after famous hotels of early 20th century such as the Grandhotel Pupp, and the Czech spa town of Karlovy Vary. In the 1930s, at the height of its opulence, the hotel is a pastel shade of pink stucco, the corridors are wide and it is palatial, crowded and buzzing with activity. Each room we see is sumptuously over-decorated, and even the service passages and staff rooms are minutely detailed.

Halfway through the film, a war breaks out, and, The Grand Budapest is commandeered by a fascistic looking army and filled with soldiers and red-and-black banners.

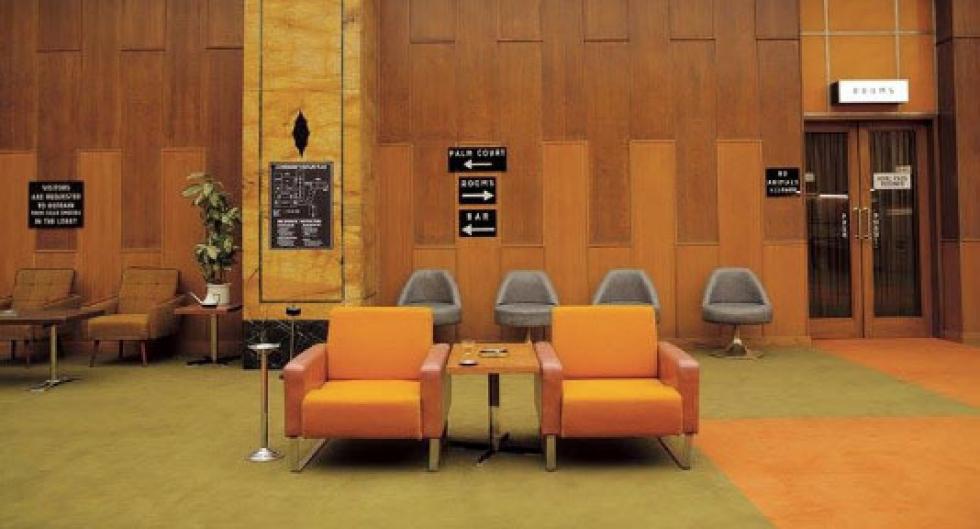

By the time we have reached 1968, the hotel is shabby and unkempt, almost empty. It has become a drab orange-and-brown relic that has fallen into disrepair behind the Iron Curtain. The external facade is no longer pastel pink, but unfinished grey stone. The pastel shades of the interior replaced with cheap looking orange plastic and green carpets. The lobby is smaller and feels cramped and uncomfortable. Vending machines replace the waiting staff, and officious signage tells the few patrons what they may and may not do. It has become a shadow of it’s former self, and the film’s narrator explains it is demolished not long after the story concludes.

When making Arch Viz images, we are not always telling a story with the depth of Brazil, or The Grand Budapest Hotel, nor do we usually have the budget or running time of a Hollywood feature film. We can however try to take a more creative approach in sketching out a believable world in our images.

In the image below titled “The Belvedere”, the brief was to express elegance and a sense of grandeur. A belvedere (from the Italian for "fair view") is an architectural feature of a building, designed and situated to look out upon a pleasing scene.

The dusk backplate shows off the New York cityscape at its finest. The early evening invokes the potential of the night ahead, and coupled with the model’s glamourous attire, this creates a sense of anticipation. She looks down at the city below from the high window, contemplating her night at the most important event of the year. The champagne and pomegranate on the table in the foreground speak of a sophisticated and refined palette. We know we are in the presence of an aesthete.

Imbuing an image with a simple narrative in this way can really help to enhance what is a fairly simple scene. We can try to question the spaces we are dressing and the motives of the people who will come to inhabit them. Who will live here? What are their aspirations? What is their story, and how can we best tell it through the images we craft?

Tom Fitzpatrick

15 November 2016